The EUIPO has ruled on whether Prada can protect their triangle pattern, referred to by Prada themselves as being their “iconic Triangle”. The EUIPO Board of Appeal has ruled that the pattern would not be inherently distinctive, but what does this mean?

Some background to the Prada Triangle case

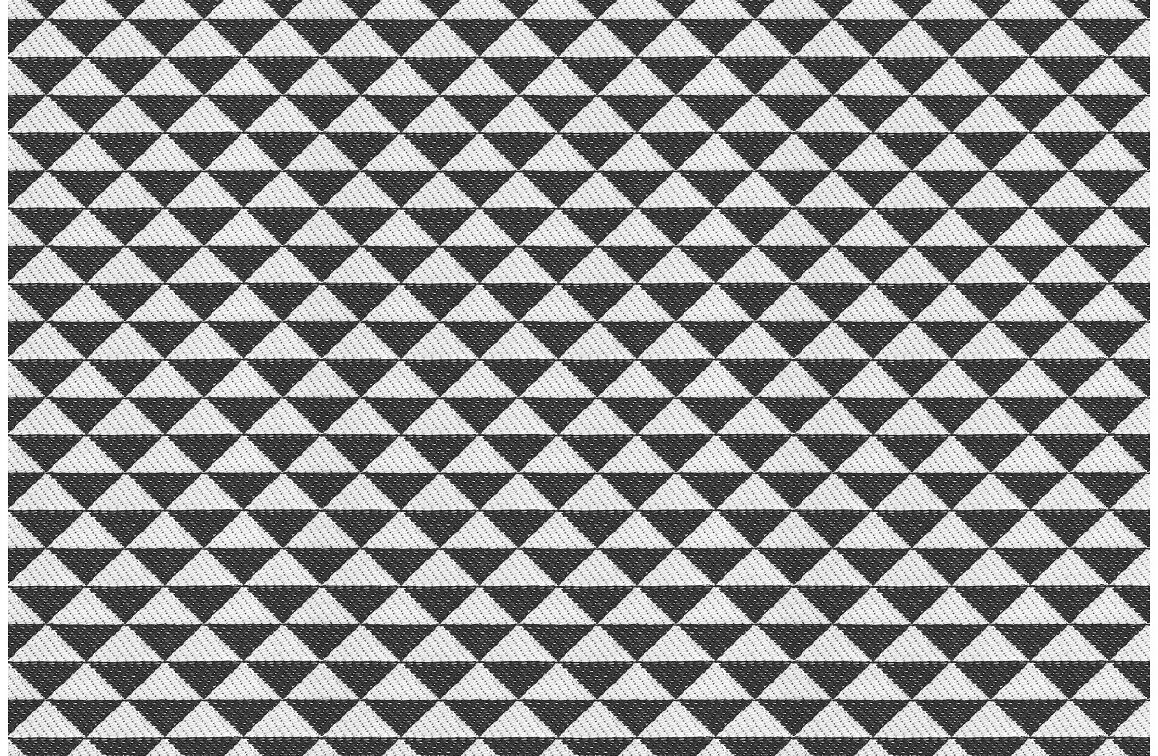

Prada applied to register its triangle pattern (depicted below) in April 2022 as an EU trade mark (EUTM Application No 018683223) in relation to the goods and services in Classes 3, 9, 14, 16, 18, 20, 24, 25, 27, 28, 35, which includes everything from non-medicated cosmetics and toiletry preparations to clothing and video games.

The Examiner prosecuting the application raised the objection that the trade mark lacked inherent distinctiveness pursuant to Article 7(1)(b) EUTMR for the majority of the goods and services applied for.

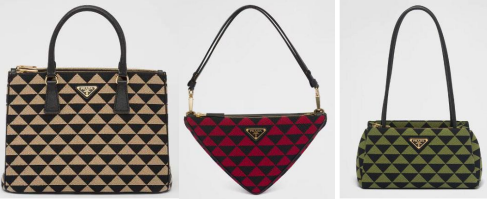

Prada argued that the iconic upside-down isosceles triangles had clearly become their iconic signature; they had already successfully registered “Triangle” figurative trade marks before with the EUIPO; and that the pattern had been extensively used and promoted.

The case was refused by the Examiner for the majority of goods and services applied for and was allowed only for certain classes of goods and services that were of little use to Prada, including computer software, business administration and marketing research.

Prada appealed the decision but specifically refrained from relying on acquired distinctiveness through use, relying solely on their inherent distinctiveness argument.

Decision of the Second Appeal Board

To achieve inherent distinctiveness, in the absence of verbal elements or other elements that could allow the sign to be perceived by consumers prima facie as trade mark, the EUIPO generally considers that the overall impression created by simple shapes following a pattern, as in the mark applied for, is devoid of any distinctive character. In other words, consumers will not perceive the pattern as a badge of trade origin, but merely as a decorative pattern of a style which is commonplace in the field of textiles and other industries concerned in the case at issue. This is outlined in the EUIPO trade mark guidelines.

The Board of Appeal concluded in its decision that the triangle-shaped pattern is indeed “a basic and commonplace figurative pattern” and “does not contain any notable variation in relation to the conventional representation of a triangle-shaped pattern and is the same as the traditional form of such a pattern”.

Specifically, regarding clothing, textiles and similar goods, the Board of Appeal agreed with the Examiner to find that the pattern is “commonly used” and “the targeted public would merely perceive the repeating pattern as a typical design of decorative elements, as opposed to a trade mark”. The average consumer would consider the Prada pattern “as an attractive detail of the product in question, or as a banal decorative element, rather than as an indication of its commercial origin”.

As such, the Board of Appeal found the pattern lacked inherent distinctiveness. The Board of Appeal could not say whether the triangle pattern could have acquired distinctiveness through its use because Prada did not rely on Article 7(3) EUTMR in the appeal.

Inherent vs Acquired Distinctiveness

Although it was claimed that the pattern was “iconic”, which could lead to a finding of distinctive character acquired through use, Prada did not rely on the acquired distinctiveness of the sign and as such, the EUIPO could only assess its inherent distinctiveness in respect of a very wide range of goods, and which the application was found to be lacking.

Proving that a mark has acquired distinctiveness is a means to bypass a lack of inherent distinctiveness. However, this is no easy task as the mark must have acquired distinctiveness through a significant portion of the EU to be accepted by the EUIPO.

In this case at least, it appears that acquiring distinctiveness is the only way this triangle pattern may be accepted by the EUIPO for goods and services of use to Prada.